Stainless steel in seawater environments is both a powerful solution and a potential trap. Many people assume that “stainless” means “rust-proof,” only to discover pitting, staining, or even perforation after a few years in service.

From coastal architecture and marine equipment to desalination plants and seawater filtration systems, the right stainless steel can deliver long life with relatively low maintenance. The wrong grade, surface finish, or design detail, however, can corrode quickly in salt-rich conditions.

This guide explains:

Whether you’re an engineer, project manager, or buyer, this article will help you make more confident decisions about using stainless steel in seawater.

Seawater is far more corrosive than fresh water because of its chemistry and the environments where it’s found. Several factors work together:

In short, seawater is a dynamic, chloride-rich, oxygen-containing electrolyte that exposes weaknesses in both material choice and design.

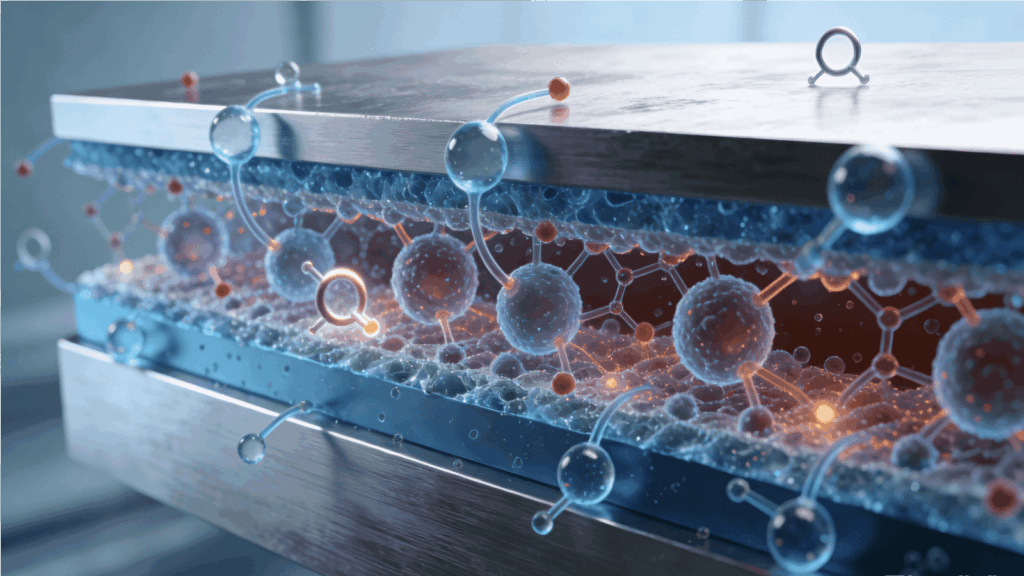

Stainless steel contains at least about 10.5% chromium. In the presence of oxygen from air or water, chromium forms a very thin, stable oxide layer on the surface known as the passive film. This film separates the underlying metal from the environment and can self-heal if lightly scratched, as long as oxygen is available.

Higher-alloy stainless steels with more chromium and molybdenum build a stronger, more stable passive film, which generally improves performance in seawater.

Even with a passive film, stainless steel can still suffer localized corrosion in seawater:

Understanding these mechanisms is essential when selecting grades and designing structures that will face seawater.

When you evaluate stainless steel for a seawater application, think in terms of environment plus design, not just alloy name.

Type of exposure matters. Coastal atmosphere, splash and spray zones, tidal zones, and continuous immersion all impose different levels of risk. A handrail in a seaside city faces different challenges than a pump casing in a desalination plant.

Temperature and climate affect the severity of attack. Warm or tropical seas are more aggressive than cold water, and solar heating can create locally hot spots around the waterline.

Oxygen availability and flow influence whether corrosion is uniform or localized. Well-aerated, flowing seawater may promote general corrosion, while stagnant pockets promote crevice corrosion.

Surface finish and cleanliness are critical. Smooth, clean, well-finished surfaces resist attack far better than rough, contaminated, or poorly cleaned welds.

Design details such as crevices, sharp corners, dead legs, and dissimilar metal contacts can make the difference between a long service life and early failure.

Finally, maintenance level sets the reality check. A component that can be rinsed and inspected regularly can tolerate more risk than a remote, buried, or submerged part with little or no access.

The table below summarizes typical relative performance of common stainless steel families in seawater. It is qualitative by design. Always confirm with standards, supplier data, and, where needed, testing for your exact conditions.

“Generally suitable” assumes sound design, smooth finish, and appropriate maintenance.

| Grade / Family | Key Alloying Features | Typical Seawater Suitability* | Example Applications |

| 304 / 304L | ~18% Cr, 8% Ni | Suitable for coastal atmosphere away from direct spray. Generally not recommended for immersion or severe splash zones. | Coastal trim, handrails sheltered from direct seawater |

| 316 / 316L | Similar to 304 + ~2–3% Mo | Widely used in coastal atmosphere and many splash zones, especially in cooler climates and with good design. Limited for immersion in warm, stagnant seawater. | Marine hardware, deck fittings, exposed architectural elements |

| 303 | Free-machining version of 304 (higher S) | Reduced corrosion resistance due to sulfur. Best restricted to non-immersion components in less aggressive marine atmospheres. | Machined fasteners and fittings in sheltered locations |

| Duplex 2205 | Austenitic–ferritic; elevated Cr, Mo, N | Good resistance to pitting and crevice corrosion. Suitable for many immersion and splash conditions with appropriate design and fabrication. | Structural components, cranes, seawater systems, filters |

| Super Duplex (e.g., 2507) | Higher Cr, Mo, N than 2205 | Very high resistance to seawater corrosion, including immersion in severe conditions. | Offshore structures, risers, critical seawater cooling |

| Super Austenitic (e.g., 6Mo grades) | High Ni, Mo, N | Excellent resistance in warm, high-chloride seawater where 316 fails. | Desalination plants, high-specification filtration, process equipment |

| Nickel Alloys (Monel, Inconel, etc.) | Ni-rich alloys | Used when seawater conditions exceed stainless capabilities or when design life requirements are extreme. | Deepwater and high-temperature components, critical offshore equipment |

Even the best grade will fail early if the design is poor. Field experience shows that crevices and bad surface condition are among the main reasons for stainless steel failures in seawater.

Key design practices include:

Good design can often extend the life of a “lower” alloy further than poor design can with a more expensive grade.

Stainless steel is low maintenance, not zero maintenance, especially in seawater.

In coastal atmospheres and splash zones, periodic fresh-water rinsing removes salt deposits and slows pitting initiation. Scheduled inspections help you catch tea-staining, rust streaks, or early pitting around welds and joints before they become structural issues.

In immersed systems such as seawater filtration, cooling, and intake structures, cleaning biofouling and deposits is essential. Under-deposit corrosion beneath marine growth or sediment can progress unnoticed if inspection and cleaning are neglected.

A simple maintenance log that records inspection dates, observed issues, and corrective actions quickly becomes a valuable feedback tool for improving material selection and design on future projects.

Stainless steel is used across many seawater-related industries:

Coastal architecture relies on stainless steel for handrails, balustrades, façades, and street furniture that must survive salt-laden air and occasional spray. Marine equipment and shipboard hardware depend on stainless for deck fittings, ladders, and small structural components that see regular wetting and drying. Offshore oil and gas projects use duplex and super duplex steels for structural members, cranes, pipework, and process equipment in demanding splash and immersion zones. Desalination and seawater cooling systems incorporate stainless or higher alloys for intake screens, filters, and heat exchangers. Aquaculture and water treatment facilities use stainless steel cages, pumps, and pipework in brackish and full seawater environments.

Each sector balances corrosion risk, budget, and maintenance access differently, which is why no single stainless grade fits every seawater application.

A structured selection process helps you avoid costly mistakes:

First, define the environment as precisely as possible. Clarify whether you are dealing with coastal atmosphere, splash and spray, tidal cycling, or continuous immersion, and capture typical and peak temperatures, flow conditions, and contamination risks.

Next, set performance expectations. Decide how long the component must last, what level of cosmetic change is acceptable, and how often maintenance can realistically happen. A decorative handrail with easy access can tolerate more visible change than a critical hidden component.

Then, shortlist candidate grades that match the environment and expectations. For mild coastal atmospheres, 304 or 316 may be sufficient. For severe splash, warm immersion, or limited access, duplex or higher-alloy stainless steels are usually more appropriate.

After that, review fabrication and design implications. Check availability of sections and plates, welding procedures, finishing requirements, and compatibility with adjacent materials and any cathodic protection system.

For high-risk or novel applications, validate the choice using supplier data, corrosion charts, case studies, and, where justified, laboratory or field testing under representative conditions.

Finally, involve experienced partners. Materials engineers, corrosion specialists, and stainless steel suppliers with real seawater experience can help refine grade selection and design details before fabrication starts.

Using stainless steel in seawater successfully is not a matter of picking a “marine grade” label and hoping for the best. It requires a clear understanding of how seawater attacks metals, realistic expectations of what each stainless family can handle, and attention to design and maintenance.

If you start by defining the environment, then select the alloy, then refine the design and maintenance plan, you are far more likely to achieve the service life you expect. Treat stainless steel in seawater as a system that combines material, environment, design, and maintenance, and you turn a corrosion risk into a long-term asset.

Walmay will help match the right stainless product form and specification for your application, confirm quantities and packing needs, and provide requested documents based on order requirements.