To temper steel by heating and cooling is one of the most important heat treatment processes in metalworking. Tempering is used to adjust hardness, strength, and toughness after steel has been hardened, making it suitable for real-world applications where brittleness would otherwise cause failure.

This article explains what tempering is, how steel is tempered through controlled heating and cooling, why the process is necessary, and where tempered steel is commonly used.

To temper steel means to reheat hardened steel to a controlled temperature below its critical point and then cool it, usually in air. This process reduces brittleness while maintaining sufficient hardness and strength.

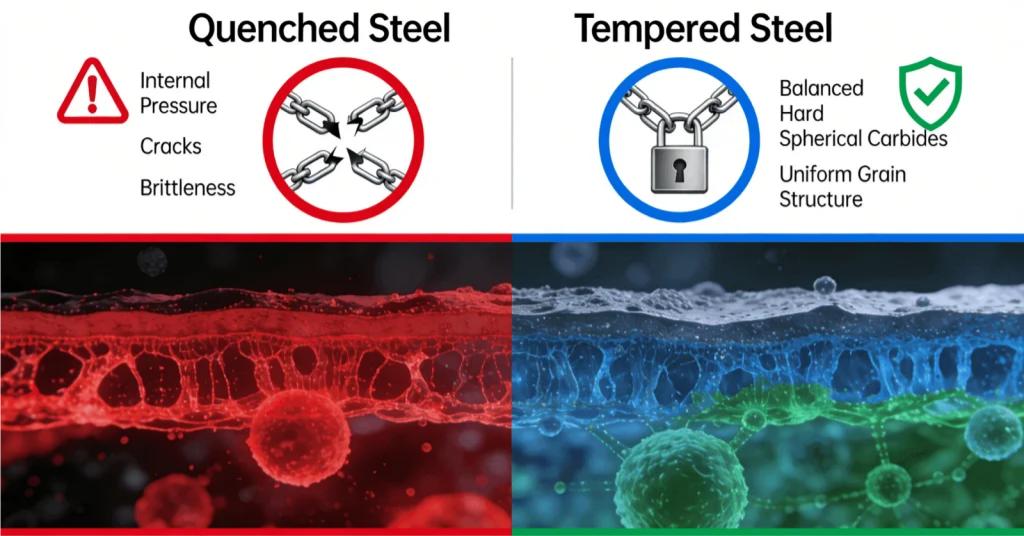

Tempering is almost always performed after hardening, which involves heating steel to a high temperature and rapidly cooling it (quenching). While quenching increases hardness, it also makes steel brittle. Tempering corrects this imbalance.

When steel is hardened by rapid cooling, its internal structure becomes very hard but unstable. Without tempering, hardened steel can crack, chip, or fail under stress.

Tempering steel by heating and cooling:

The goal is to achieve the best balance between hardness and toughness for the intended application.

Before tempering, steel is hardened by:

This creates a very hard but brittle structure known as martensite.

To temper steel, the hardened steel is reheated to a lower temperature, typically between 150°C and 650°C (300°F to 1200°F), depending on the desired properties.

The steel is held at this temperature long enough to allow controlled changes in its internal structure.

After heating, the steel is cooled slowly, usually in still air. Unlike hardening, rapid cooling is not required.

This controlled cooling:

The result is steel that is strong, durable, and far less brittle than fully hardened steel.

Tempering alters the hardened martensitic structure of steel:

These changes explain why tempered steel performs better under real operating conditions than fully hardened steel.

In some steels, especially carbon steel, surface oxide colors appear during tempering and indicate temperature:

While not precise, temper colors have traditionally helped blacksmiths and machinists judge tempering temperature.

Steel tempered by heating and cooling is used in many critical applications:

Without tempering, these components would be too brittle for safe and reliable use.

Improper tempering can reduce performance or cause failure:

Careful temperature control and consistent processing are essential.

To temper steel by heating and cooling is a critical step in achieving usable mechanical properties. By reheating hardened steel to a controlled temperature and allowing it to cool slowly, tempering reduces brittleness, relieves internal stress, and improves toughness while maintaining strength.

Whether used in tools, machinery, automotive parts, or structural components, tempered steel delivers the balance of hardness and durability required for demanding applications. Understanding the tempering process ensures steel performs safely, reliably, and efficiently throughout its service life.

Walmay will help match the right stainless product form and specification for your application, confirm quantities and packing needs, and provide requested documents based on order requirements.